What is classification?

Classification is the process of sorting items into categories. The whole set you’re classifying — animals, college courses, tools, or anything else — is the genus; your job is to subdivide that genus into species so each item has a clear place. There are often many possible ways to divide a genus, but some divisions are better than others. The rules of classification help us choose the best, most useful divisions.

Why good classification matters

A good classification makes it easy to find, compare, reason about, and act on items. Bad classification causes confusion: overlapping categories, gaps that leave items unassigned, or groupings that tell you almost nothing useful about the members.

Rule 1 — Use a consistent principle (mutually exclusive & jointly exhaustive)

The first rule in any system of classification is consistency in the principle you use to divide the genus. Two formal standards follow from that:

Mutually exclusive: Different species should not overlap. Every item must belong to only one species under the chosen principle. If categories overlap (e.g., art and introductory when classifying courses), you cannot assign certain items unambiguously.

Jointly exhaustive: The species taken together should cover the entire genus. Every item must fall into one of the species; otherwise the classification leaves gaps.

When you diagram a classification you can show the guiding principle in brackets under the genus name (for example: Furniture [function] → table | bed | chair). The species then reflect consistent differences with respect to that single principle.

Common failures to follow Rule 1

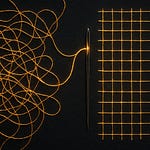

An inconsistent classification mixes different dividing principles (ownership, condition, training, shape, etc.). Such mixes produce overlapping and chaotic categories that are useless for clear reasoning or action.

Rule 2 — Prefer essential attributes when possible

The second rule helps choose among multiple consistent divisions: base your classification on essential attributes rather than superficial ones.

An essential attribute is a fundamental property that makes a thing what it is. Classifying by essentials groups items that are fundamentally similar and separates things that are fundamentally different.

A non-essential attribute (superficial) — such as color, transient condition, or arbitrary ownership — may cluster items together that otherwise have little in common, making the classification unhelpful.

Examples: animals and furniture

Animals: Biologists classify animals by essential principles—mode of reproduction (egg-laying vs. live birth), internal physiology (vertebrate vs. invertebrate), thermoregulation (warm-blooded vs. cold-blooded), means of locomotion (swimming, flying, crawling). These reflect fundamental biological functions (survival and reproduction), so groupings are informative: similar groups tend to share many attributes.

Color-based animal groups: Classifying animals by color (gray, red, green…) puts together elephants, mosquitoes, and certain sharks just because of superficial similarity — a classification that tells you little of value about the animal’s behavior, needs, or risks.

Furniture: For man-made objects the essential attribute is usually function: knowing a tool’s purpose explains its shape, material, and structure. Interior designers, however, may legitimately choose style as essential for their purpose (Danish vs. Colonial furniture).

When multiple principles are necessary

Complex phenomena often require multiple consistent principles (e.g., biologists use anatomy, behavior, genetics). That’s fine — but be careful: when using several principles, structure the taxonomy so species remain mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive. Multiple principles must be applied in a disciplined way (hierarchical or multi-axial classification) rather than mixing unrelated criteria randomly.

A cautionary illustration (Borges’ faux taxonomy)

Jorge Luis Borges’ imaginary categories (animals that belong to the emperor; those drawn with a very fine brush; those that tremble as if mad; etc.) show what goes wrong when classification lacks a consistent principle. Categories overlap, many items fit several headings, and the single catch-all “others” hides the absence of coherent principles. This is exactly what to avoid.

Applying rules of classification to people and institutions

Classification is not inherently problematic — we classify students, applicants, products, and organizations all the time. The ethical and practical problem arises when we classify by attributes that are not essentially related to the purpose at hand.

Example: Employment — A fair employer classifies applicants by ability, training, and character (attributes essentially related to job performance) rather than by race or sex (non-essential for performance).

Example: Corporations — Classifying companies by function (producer vs. service; non-profit vs. for-profit) is usually essential and useful. A classification by CEO height would be superficial and useless.

Determining what is “essential” often requires expertise and judgment; there is no mechanical test. Reasonable people may disagree. Still, seeking essential attributes generally improves clarity and usefulness.

The role of purpose in choosing essential attributes

Classification serves a purpose — your goal influences what you take as essential. For general biological understanding, anatomy and reproduction are essential. For an interior designer, style may be essential. Both classifications can be valid within their purposes; the key is to be explicit about the guiding principle and to follow it consistently.

Quick checklist: building a good classification (summary of rules)

Decide your purpose — What will this classification be used for?

Choose a principle (or coherent set of principles) that serves that purpose.

Ensure mutual exclusivity — species should not overlap under your principle(s).

Ensure joint exhaustiveness — every member of the genus should be assignable.

Prefer essential attributes when they are available and relevant.

When using multiple principles, structure them hierarchically or orthogonally so categories remain non-overlapping and complete.

Be explicit — name the principle(s) in diagrams or labels so users understand the logic.

Final note on judgment and disagreement

There is no mechanical shortcut to distinguish essential from non-essential features in every domain. Some domains (like chemistry) have deep research to justify essentials; others (human institutions, policy) require normative judgment. Expect debate — but aim for clarity: state your purpose, be consistent about principles, and prefer fundamental attributes that make the classification useful.